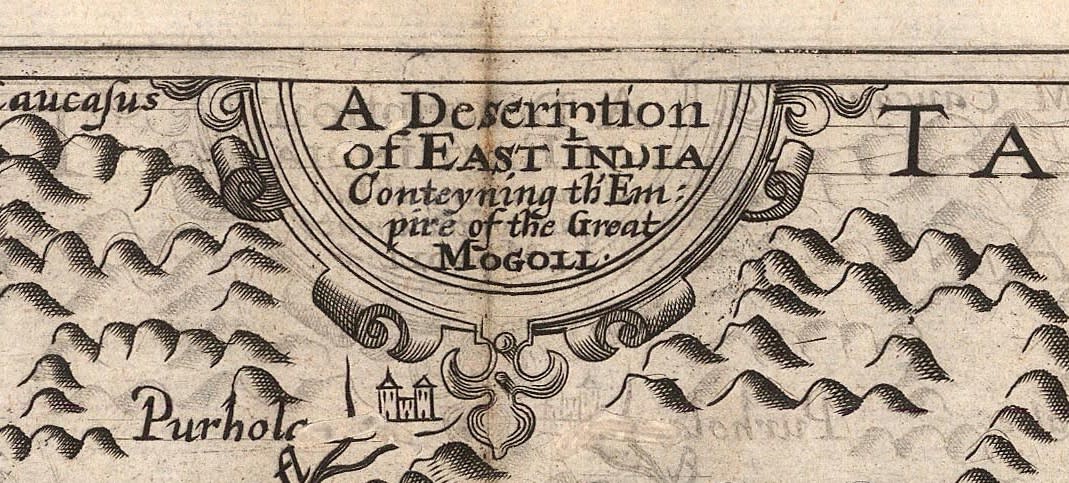

The focus of our Map of the Month this time is “A Description of East India Conteyning th’Empire of the Great Mogoll.”

This is the first regional map of India in English. It is sourced from primary documents obtained personally by its author Thomas Roe and was drawn by one of the greatest Polar explorers, William Baffin. Such is its importance, fame and influence that it is one of the few cartographic documents that has its own name: the Baffin-Roe Map.

Its geography was used extensively for over a hundred years and it was a primary source for cartographers of the Dutch Golden Age such as Blaeu and Jansson as well as their peers in other parts of Europe such as Sanson in Paris and Coronelli in Venice.

The background to the map is fascinating.

A Portuguese galleon was captured on its return from India by an English privateer in the late 16th century and its unloading in Portsmouth Harbour caused a sensation; crowds gathered to witness a cargo of spices, silks, ivory, jewels and hides the like of which they had never seen before. It was one thing to read or be told tales of riches from the far side of the world but it was quite another to actually witness the evidence. It was even more galling to imagine that Portugal would receive fleets of ships such as these every year. Thus, in 1600 Elizabeth I granted a Royal Charter to the “Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies”, which quickly became known as the East India Company.

Initial voyages sponsored by the Company were fraught with difficulties as Portuguese and Dutch merchants enjoyed a monopoly on trade to and from India. So, in 1612, King James I asked Sir Thomas Roe to travel to the court of the Moghul Emperor and secure his approval for British commercial interests in his Empire.

Roe was a man of great influence, friend to James the First, his son Henry and his daughter Elizabeth, the Winter Queen. He also seems to have been a diplomatic troubleshooter for James, travelling widely throughout Europe, Asia and the New World. Not only did he travel to India and succeed beyond the Company’s wildest dreams, he was later sent to the Court of the Ottoman Emperor as the British ambassador, secured the release of several hundred English slaves from Algiers, negotiated a treaty with Denmark and Danzig and was instrumental in settling a conflict between Sweden and Poland, thus allowing Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, to take a decisive part in the Thirty Year’s War on the side of the Protestant faction.

Roe embarked in 1614 and arrived in Surat, on the West coast of India. This was the sub-continent’s commercial gateway with Europe and it was already full of Dutch and Portuguese trading factories. He managed to secure an audience with Prince Khurram, the Crown Prince, who was to become Emperor Shah Jahan and later was responsible for the construction of the Taj Mahal. He must have made quite an impression as Khurram invited him to travel with his Court to Agra to meet his father, the Emperor Jahangir. Roe spent the next three years there and developed a personal relationship with Jahangir; both men held each other in great esteem and Roe managed to secure those precious favoured trading conditions for English merchants within the Empire.

In 1618, Roe returned to England on a ship in the service of the East India Company, The Anne Royal. While on board, he met the master’s mate, William Baffin. Baffin was a seasoned sailor, traveller, explorer as well as an accomplished chart maker. He had been born into poverty but through his own ambition, managed to educate himself and had been part of the crew during several voyages to the far North, looking for the Northwest Passage as well as sailing to Greenland and Spitsbergen. His contribution and importance to these voyages must have been considerable as both Baffin’s Bay and Baffin’s Island, geographical features between Greenland and Canada, were named after him.

In this latest voyage, in the service of the Company, he had already been to the Persian Gulf as well as Yemen and the Red Sea. He wrote journals of his experiences and made charts of many of the regions to which he travelled. Roe and Baffin conferred and during the return voyage, the latter drew a map of the Moghul Empire based on Roe’s personal notes, descriptions, documents and local maps he had managed to obtain and record during his Embassy.

The Baffin-Roe Map, as it has now become known, was published in 1619 and was sold as a loose sheet upon Roe’s return. One single, dated example has been preserved in the King’s (George III) Topographical Collection, held in the British Library. It is not known who published it but an imprint on the lower left advertises that it was available for purchase at the premises of Thomas Sterne, Globemaker, in St. Paul’s Churchyard.

Roe compiled his journals under the title “The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe To The Court Of The Great Mogul, 1615-1619.” Curiously, we cannot find any evidence that the journal was published upon Roe’s return. This may be because it took him longer than he expected to compile the work. After all, he was sent to Constantinople as British Ambassador almost immediately after his return, in 1621; or it was published in such small numbers that no example of this early version of the Journal survives. However, its importance must have been quickly recognised as it was used as the primary source for descriptions of the Mogul Empire throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. In fact, such was its importance and influence that it is still being re-issued to the present day, with the last edition coming out in 2015.

Thankfully, in 1625, excerpts of Roe’s journal were published by Samuel Purchas in “Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas his Pilgrimes contayning a History of the World in Sea Voyages and Lande Travells, by Englishmen and others”. This was a vast collection of great travel accounts, centering mainly on English explorers, mariners and diplomats. Based both on the collections of Richard Hakluyt (after whom the Hakluyt Society is named) and Purchas’s own papers, this four volume work became the pre-eminent source for early English travel and exploration. This seems to be the first time that at least parts of Roe’s Journal appeared in print. The whole work was illustrated with a series of maps.

Therefore, the Purchas edition of the Baffin-Roe map is certainly the first commercially available version of this piece in the present day. It was somewhat smaller than the publication of six years earlier and Baffin’s name has now been removed from the lower centre of the map, together with a cartouche bearing the date on the lower left corner as well as Sterne’s name and location. The name of the engraver, Reynold Elstracke, is present on both versions. Excluding those differences, the maps are the same.

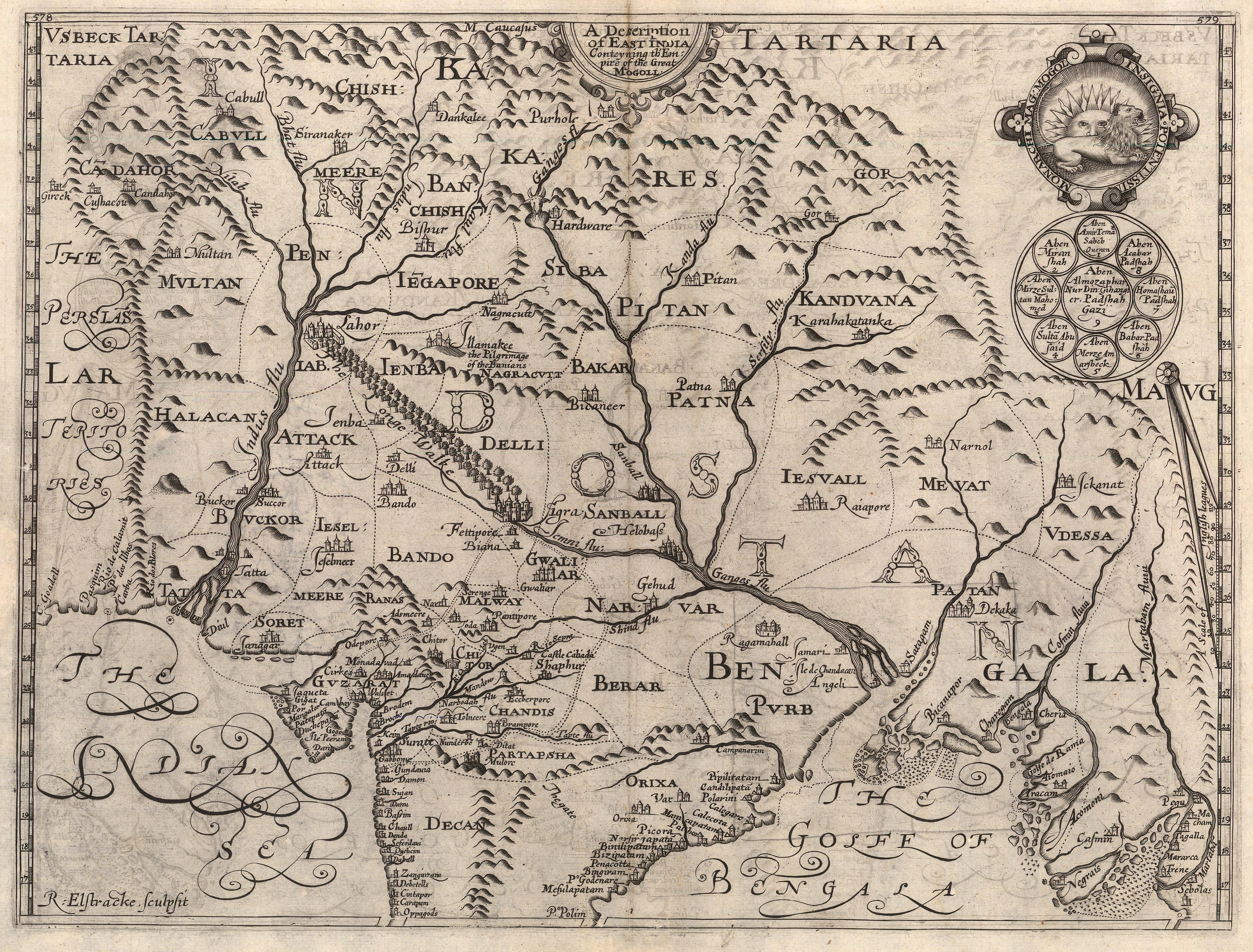

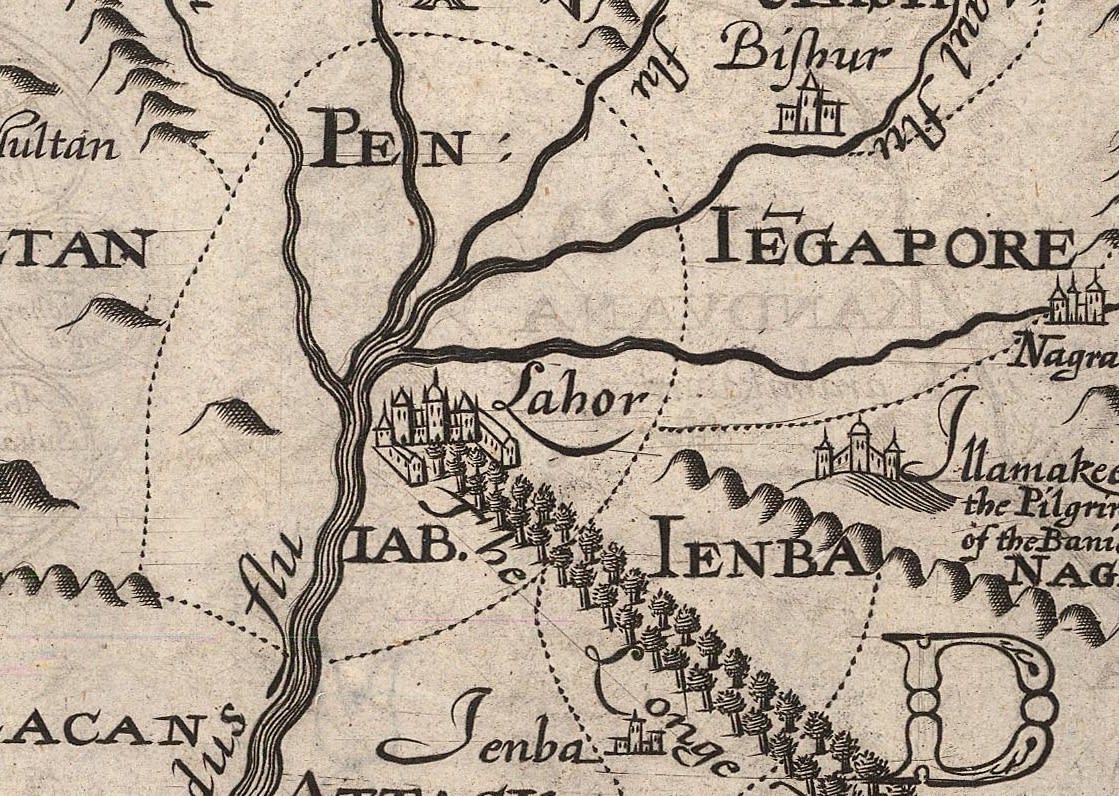

Geographically, the map encompasses the extraordinary size of the Moghul Empire, stretching from the Eastern border of Persia, through modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, Northern India as far south as the Deccan, and then East to Bangladesh and Western Myanmar. The map shows clear divisions of Moghul administrative regions or subas. It also correctly shows the Empire having a vast mountain range as its Northern border for the first time. Two of the great rivers of India, the Indus and the Ganges, along with their many tributaries, are shown with greatly corrected courses and sourcing from these northern mountains, again correctly. Another major step forward is the relatively accurate placement of the Indus delta.

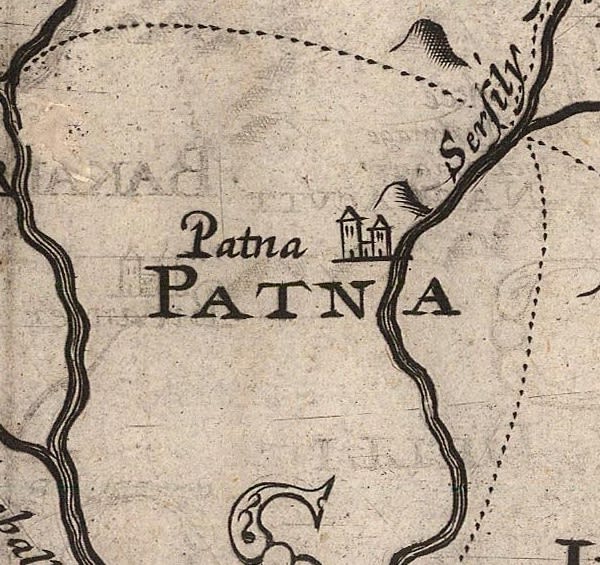

Taking a more detailed look at the map, Roe notes the multitude of coastal settlements which would have been known to Europeans through Portuguese and Dutch sources, notably Linschoten’s famous map of the Indian Ocean; however, this was the first time that a regional map of the sub-continent had become available and there was a whole collection of new exotic names and settlements that appeared on a Western map for the first time. These included “Patna”,”Agra”, “Peniab” and “Siranaker” among others.

There are other features on this map which would have enthralled the public: “Hardware” modern Haridwar, is notable for many reasons, one of them being the city where the River Ganges enters into the plains of India; it is said that the river flows over a large rock that resembles a cow’s head. This is portrayed on the map with a charming engraving. Again, this is the first time that Haridwar appears on a Western map.

Dominating the left side of the engraving is a stretch of trees leading from Agra to “Lahor” marking a part of the Grand Trunk Road linking the two cities. The trees are a reference to Jahangir’s order to plant mulberry trees on either side of the road between Agra and the Indus, which in turn was part of the tradition of Moghul Emperors to build, landscape and plant large, exotic gardens. These have now become known as the Moghul Gardens. This feature on the map is entitled “The Longe Walke”.

Rather modestly, Roe also marks his own route on the map, starting just south of Surat, leading to Agra and then returning to Cambay or modern Khambhat.

The upper right of the map bears two potent symbols of Mogul power: the first is the Imperial symbol of the Moghuls, a lion crouching in front of the sun and below is the Imperial Seal, a large central sphere, surrounded by eight smaller spheres within a circle; the name of the ruling Emperor, Jahangir, is in the centre while previous emperors are named in the smaller spheres. The names have been faithfully translated into English.

The map was copied almost immediately after its publication, appearing in atlases and travel books in Holland, France, Italy and Germany well into the 18th century. Although these later maps were revised and amended, their fundamental information as well as their general geographical area can ultimately always be traced back to the Baffin-Roe Map.

Written by Peter Stuchlik, 2016 ©

The focus of our Map of the Month this time is “A Description of East India Conteyning th’Empire of the Great Mogoll.”

This is the first regional map of India in English. It is sourced from primary documents obtained personally by its author Thomas Roe and was drawn by one of the greatest Polar explorers, William Baffin. Such is its importance, fame and influence that it is one of the few cartographic documents that has its own name: the Baffin-Roe Map.

Its geography was used extensively for over a hundred years and it was a primary source for cartographers of the Dutch Golden Age such as Blaeu and Jansson as well as their peers in other parts of Europe such as Sanson in Paris and Coronelli in Venice.

The background to the map is fascinating.

A Portuguese galleon was captured on its return from India by an English privateer in the late 16th century and its unloading in Portsmouth Harbour caused a sensation; crowds gathered to witness a cargo of spices, silks, ivory, jewels and hides the like of which they had never seen before. It was one thing to read or be told tales of riches from the far side of the world but it was quite another to actually witness the evidence. It was even more galling to imagine that Portugal would receive fleets of ships such as these every year. Thus, in 1600 Elizabeth I granted a Royal Charter to the “Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies”, which quickly became known as the East India Company.

Initial voyages sponsored by the Company were fraught with difficulties as Portuguese and Dutch merchants enjoyed a monopoly on trade to and from India. So, in 1612, King James I asked Sir Thomas Roe to travel to the court of the Moghul Emperor and secure his approval for British commercial interests in his Empire.

Roe was a man of great influence, friend to James the First, his son Henry and his daughter Elizabeth, the Winter Queen. He also seems to have been a diplomatic troubleshooter for James, travelling widely throughout Europe, Asia and the New World. Not only did he travel to India and succeed beyond the Company’s wildest dreams, he was later sent to the Court of the Ottoman Emperor as the British ambassador, secured the release of several hundred English slaves from Algiers, negotiated a treaty with Denmark and Danzig and was instrumental in settling a conflict between Sweden and Poland, thus allowing Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, to take a decisive part in the Thirty Year’s War on the side of the Protestant faction.

Roe embarked in 1614 and arrived in Surat, on the West coast of India. This was the sub-continent’s commercial gateway with Europe and it was already full of Dutch and Portuguese trading factories. He managed to secure an audience with Prince Khurram, the Crown Prince, who was to become Emperor Shah Jahan and later was responsible for the construction of the Taj Mahal. He must have made quite an impression as Khurram invited him to travel with his Court to Agra to meet his father, the Emperor Jahangir. Roe spent the next three years there and developed a personal relationship with Jahangir; both men held each other in great esteem and Roe managed to secure those precious favoured trading conditions for English merchants within the Empire.

In 1618, Roe returned to England on a ship in the service of the East India Company, The Anne Royal. While on board, he met the master’s mate, William Baffin. Baffin was a seasoned sailor, traveller, explorer as well as an accomplished chart maker. He had been born into poverty but through his own ambition, managed to educate himself and had been part of the crew during several voyages to the far North, looking for the Northwest Passage as well as sailing to Greenland and Spitsbergen. His contribution and importance to these voyages must have been considerable as both Baffin’s Bay and Baffin’s Island, geographical features between Greenland and Canada, were named after him.

In this latest voyage, in the service of the Company, he had already been to the Persian Gulf as well as Yemen and the Red Sea. He wrote journals of his experiences and made charts of many of the regions to which he travelled. Roe and Baffin conferred and during the return voyage, the latter drew a map of the Moghul Empire based on Roe’s personal notes, descriptions, documents and local maps he had managed to obtain and record during his Embassy.

The Baffin-Roe Map, as it has now become known, was published in 1619 and was sold as a loose sheet upon Roe’s return. One single, dated example has been preserved in the King’s (George III) Topographical Collection, held in the British Library. It is not known who published it but an imprint on the lower left advertises that it was available for purchase at the premises of Thomas Sterne, Globemaker, in St. Paul’s Churchyard.

Roe compiled his journals under the title “The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe To The Court Of The Great Mogul, 1615-1619.” Curiously, we cannot find any evidence that the journal was published upon Roe’s return. This may be because it took him longer than he expected to compile the work. After all, he was sent to Constantinople as British Ambassador almost immediately after his return, in 1621; or it was published in such small numbers that no example of this early version of the Journal survives. However, its importance must have been quickly recognised as it was used as the primary source for descriptions of the Mogul Empire throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. In fact, such was its importance and influence that it is still being re-issued to the present day, with the last edition coming out in 2015.

Thankfully, in 1625, excerpts of Roe’s journal were published by Samuel Purchas in “Hakluytus Posthumus, or Purchas his Pilgrimes contayning a History of the World in Sea Voyages and Lande Travells, by Englishmen and others”. This was a vast collection of great travel accounts, centering mainly on English explorers, mariners and diplomats. Based both on the collections of Richard Hakluyt (after whom the Hakluyt Society is named) and Purchas’s own papers, this four volume work became the pre-eminent source for early English travel and exploration. This seems to be the first time that at least parts of Roe’s Journal appeared in print. The whole work was illustrated with a series of maps.

Therefore, the Purchas edition of the Baffin-Roe map is certainly the first commercially available version of this piece in the present day. It was somewhat smaller than the publication of six years earlier and Baffin’s name has now been removed from the lower centre of the map, together with a cartouche bearing the date on the lower left corner as well as Sterne’s name and location. The name of the engraver, Reynold Elstracke, is present on both versions. Excluding those differences, the maps are the same.

Geographically, the map encompasses the extraordinary size of the Moghul Empire, stretching from the Eastern border of Persia, through modern Afghanistan, Pakistan, Northern India as far south as the Deccan, and then East to Bangladesh and Western Myanmar. The map shows clear divisions of Moghul administrative regions or subas. It also correctly shows the Empire having a vast mountain range as its Northern border for the first time. Two of the great rivers of India, the Indus and the Ganges, along with their many tributaries, are shown with greatly corrected courses and sourcing from these northern mountains, again correctly. Another major step forward is the relatively accurate placement of the Indus delta.

Taking a more detailed look at the map, Roe notes the multitude of coastal settlements which would have been known to Europeans through Portuguese and Dutch sources, notably Linschoten’s famous map of the Indian Ocean; however, this was the first time that a regional map of the sub-continent had become available and there was a whole collection of new exotic names and settlements that appeared on a Western map for the first time. These included “Patna”,”Agra”, “Peniab” and “Siranaker” among others.

There are other features on this map which would have enthralled the public: “Hardware” modern Haridwar, is notable for many reasons, one of them being the city where the River Ganges enters into the plains of India; it is said that the river flows over a large rock that resembles a cow’s head. This is portrayed on the map with a charming engraving. Again, this is the first time that Haridwar appears on a Western map.

Dominating the left side of the engraving is a stretch of trees leading from Agra to “Lahor” marking a part of the Grand Trunk Road linking the two cities. The trees are a reference to Jahangir’s order to plant mulberry trees on either side of the road between Agra and the Indus, which in turn was part of the tradition of Moghul Emperors to build, landscape and plant large, exotic gardens. These have now become known as the Moghul Gardens. This feature on the map is entitled “The Longe Walke”.

Rather modestly, Roe also marks his own route on the map, starting just south of Surat, leading to Agra and then returning to Cambay or modern Khambhat.

The upper right of the map bears two potent symbols of Mogul power: the first is the Imperial symbol of the Moghuls, a lion crouching in front of the sun and below is the Imperial Seal, a large central sphere, surrounded by eight smaller spheres within a circle; the name of the ruling Emperor, Jahangir, is in the centre while previous emperors are named in the smaller spheres. The names have been faithfully translated into English.

The map was copied almost immediately after its publication, appearing in atlases and travel books in Holland, France, Italy and Germany well into the 18

th century. Although these later maps were revised and amended, their fundamental information as well as their general geographical area can ultimately always be traced back to the Baffin-Roe Map.

Have questions about this beautiful map? Email maps@themaphouse.com or visit our website

www.themaphouse.com to find out more!

About the author

The Map House

This is the first regional map of India in English. It is sourced from primary documents obtained personally by its author Thomas Roe and was drawn by one of the greatest Polar explorers, William Baffin. Such is its importance, fame and influence that it is one of the few cartographic documents that has its own name: the Baffin-Roe Map.

This is the first regional map of India in English. It is sourced from primary documents obtained personally by its author Thomas Roe and was drawn by one of the greatest Polar explorers, William Baffin. Such is its importance, fame and influence that it is one of the few cartographic documents that has its own name: the Baffin-Roe Map. The background to the map is fascinating.

The background to the map is fascinating. Taking a more detailed look at the map, Roe notes the multitude of coastal settlements which would have been known to Europeans through Portuguese and Dutch sources, notably Linschoten’s famous map of the Indian Ocean; however, this was the first time that a regional map of the sub-continent had become available and there was a whole collection of new exotic names and settlements that appeared on a Western map for the first time. These included “Patna”,”Agra”, “Peniab” and “Siranaker” among others.

Taking a more detailed look at the map, Roe notes the multitude of coastal settlements which would have been known to Europeans through Portuguese and Dutch sources, notably Linschoten’s famous map of the Indian Ocean; however, this was the first time that a regional map of the sub-continent had become available and there was a whole collection of new exotic names and settlements that appeared on a Western map for the first time. These included “Patna”,”Agra”, “Peniab” and “Siranaker” among others. There are other features on this map which would have enthralled the public: “Hardware” modern Haridwar, is notable for many reasons, one of them being the city where the River Ganges enters into the plains of India; it is said that the river flows over a large rock that resembles a cow’s head. This is portrayed on the map with a charming engraving. Again, this is the first time that Haridwar appears on a Western map.

There are other features on this map which would have enthralled the public: “Hardware” modern Haridwar, is notable for many reasons, one of them being the city where the River Ganges enters into the plains of India; it is said that the river flows over a large rock that resembles a cow’s head. This is portrayed on the map with a charming engraving. Again, this is the first time that Haridwar appears on a Western map. Dominating the left side of the engraving is a stretch of trees leading from Agra to “Lahor” marking a part of the Grand Trunk Road linking the two cities. The trees are a reference to Jahangir’s order to plant mulberry trees on either side of the road between Agra and the Indus, which in turn was part of the tradition of Moghul Emperors to build, landscape and plant large, exotic gardens. These have now become known as the Moghul Gardens. This feature on the map is entitled “The Longe Walke”.

Dominating the left side of the engraving is a stretch of trees leading from Agra to “Lahor” marking a part of the Grand Trunk Road linking the two cities. The trees are a reference to Jahangir’s order to plant mulberry trees on either side of the road between Agra and the Indus, which in turn was part of the tradition of Moghul Emperors to build, landscape and plant large, exotic gardens. These have now become known as the Moghul Gardens. This feature on the map is entitled “The Longe Walke”. Rather modestly, Roe also marks his own route on the map, starting just south of Surat, leading to Agra and then returning to Cambay or modern Khambhat.

Rather modestly, Roe also marks his own route on the map, starting just south of Surat, leading to Agra and then returning to Cambay or modern Khambhat. The upper right of the map bears two potent symbols of Mogul power: the first is the Imperial symbol of the Moghuls, a lion crouching in front of the sun and below is the Imperial Seal, a large central sphere, surrounded by eight smaller spheres within a circle; the name of the ruling Emperor, Jahangir, is in the centre while previous emperors are named in the smaller spheres. The names have been faithfully translated into English.

The upper right of the map bears two potent symbols of Mogul power: the first is the Imperial symbol of the Moghuls, a lion crouching in front of the sun and below is the Imperial Seal, a large central sphere, surrounded by eight smaller spheres within a circle; the name of the ruling Emperor, Jahangir, is in the centre while previous emperors are named in the smaller spheres. The names have been faithfully translated into English. The map was copied almost immediately after its publication, appearing in atlases and travel books in Holland, France, Italy and Germany well into the 18th century. Although these later maps were revised and amended, their fundamental information as well as their general geographical area can ultimately always be traced back to the Baffin-Roe Map.

The map was copied almost immediately after its publication, appearing in atlases and travel books in Holland, France, Italy and Germany well into the 18th century. Although these later maps were revised and amended, their fundamental information as well as their general geographical area can ultimately always be traced back to the Baffin-Roe Map.